Why Culture Terrifies Power

Observations on Bad Bunny, Asake, and the Fear of Uninhibited Joy

Bad Bunny wore a bulletproof vest to the Grammys.

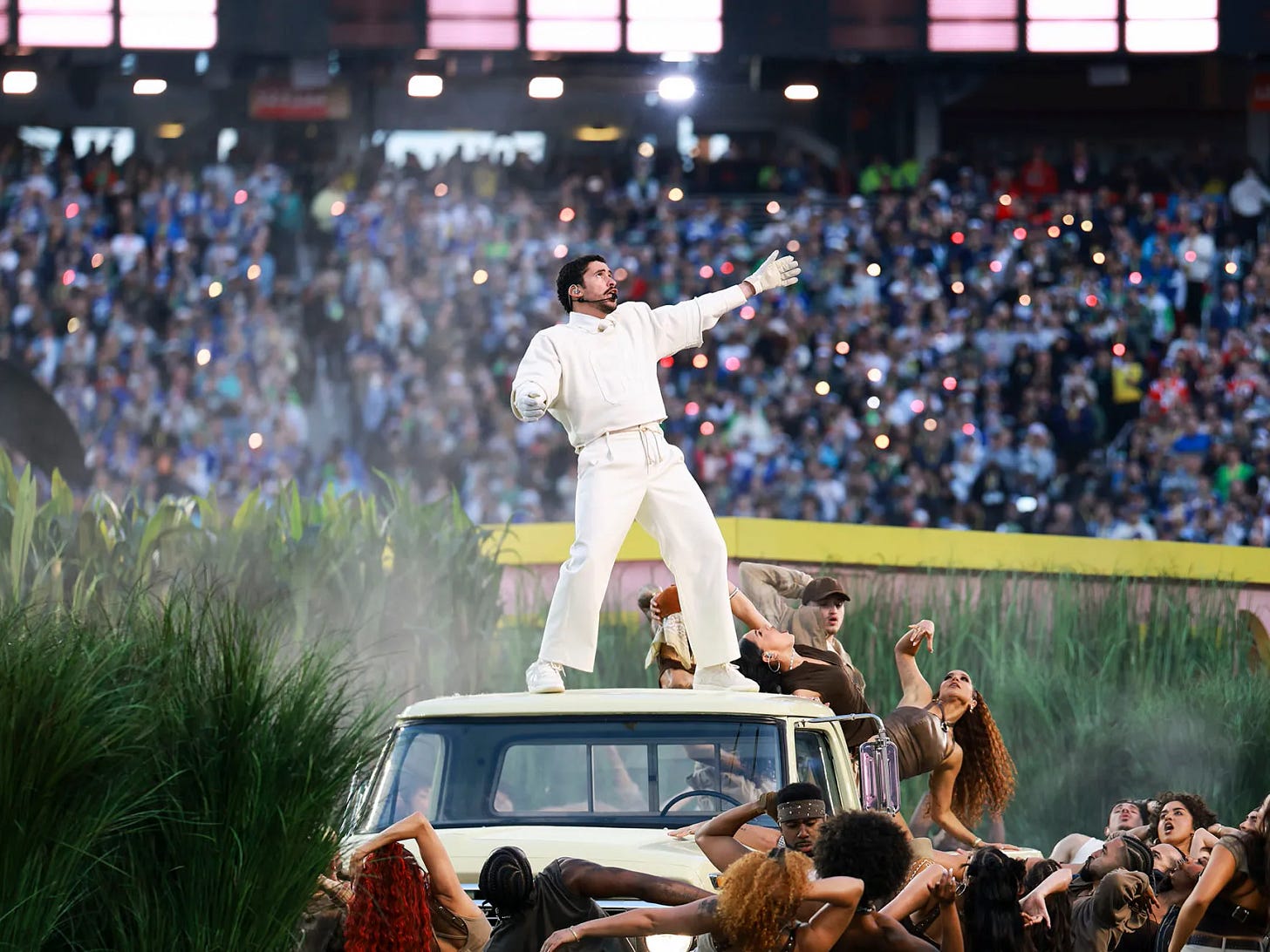

Not as a fashion statement. As protection. The biggest artist in the world right now, a Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican who performed at the Super Bowl, needed a vest because the hate had become that real, that threatening.

I’ve spent weeks watching his performances, his videos, listening to his music. I’ve researched Puerto Rican culture, watched TikToks of older Puerto Ricans hearing his songs for the first time, their faces lighting up with recognition. And I keep coming back to the same question: why is uninhibited joy this threatening?

Everything I’ve observed about Puerto Rican culture shows me people who are expressive, loving, and celebratory. It’s woven into the fabric of who they are. Their music emanates from the chants, the beats, the dance movements. Everything about it screams life. So what is it about a culture that chooses to enjoy life fully that provokes this level of hate?

This isn’t just about Bad Bunny. It’s about Asake from Nigeria exporting Yoruba culture to global stages. It’s about Hawaiian culture being commodified and controlled. It’s about why “modernity”, or rather, the powers that control what modernity means, seems positioned against certain expressions of culture. The cultures that are too alive, too communal, too difficult to package.

What Power Fears

I think the fear operates on multiple levels.

First, there’s the simple economics of cultural scarcity. If one dominant culture has built entire industries around being the “default”, the sound, the aesthetic, the reference point everyone else is measured against, then other cultures becoming equally visible, equally valuable, threatens that monopoly. It’s not just racism, though racism is certainly part of it. It’s about market share. About who gets to define what’s popular, what’s premium, what matters.

Second, there’s the problem of control. Cultures like Puerto Rican and Nigerian cultures are deeply communal, evolving over generations through collective participation. They can’t be easily reduced to a brand or a demographic. They don’t fit neatly into marketing categories. When Bad Bunny performs in Spanish and refuses to translate himself for an English-speaking audience, he’s not just making an artistic choice; he’s refusing to make his culture more digestible, more controllable.

Third, and this might be the most threatening, is the question of what these cultures actually produce in people. Joy that doesn’t need permission. Expression that doesn’t wait for approval. Communities that don’t require institutions to tell them they matter. When you’re invested in systems that depend on people feeling incomplete, inadequate, always reaching for the next thing, uninhibited cultural expression becomes dangerous. It suggests people might already have everything they need.

The Platform Problem

I’ve been watching previous Super Bowl halftime shows. Black & brown performers have owned that stage in recent years—Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar, Rihanna, now Bad Bunny. You can see why certain people want to keep a platform that massive to themselves. Over a hundred million people watch the halftime show. That’s not just visibility, that’s cultural power.

So when access to that platform shifts, the question becomes: what are the alternatives? Do marginalized cultures need to build their own platforms?

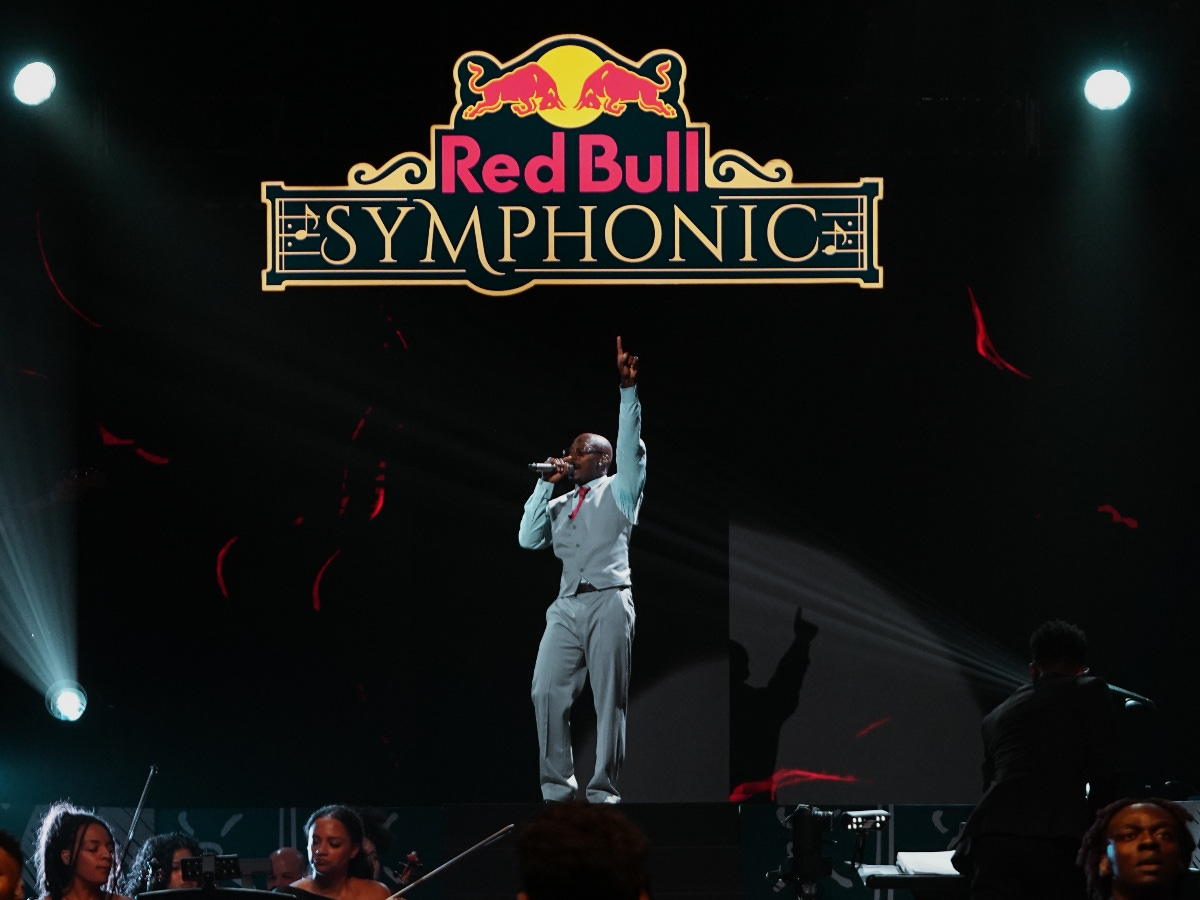

And if so, who owns those platforms? Who controls access? Red Bull funded Asake’s symphonic performance, which means corporate sponsorship made that cultural moment possible at scale. But does that sponsorship come with strings? Does it compromise what gets expressed, or does it simply acknowledge that producing culture at this level requires resources most independent artists don’t have?

The infrastructure question is real. We have artists with the catalogues, the talent, and the vision to create performances as powerful as any Super Bowl halftime show. What we often lack is the machinery around them, hundreds of dancers, concept artists, production teams, and the intellectual property that guarantees millions will watch.

This is why moments like Red Bull Symphonic matter. Asake performing with African drums and a full symphony, singing in Yoruba on a stage that size. Burna Boy bringing out African drummers and dancers at Coachella and Madison Square Garden. These aren’t just performances; they’re proof of concept. They show that the culture can hold these spaces, can command these platforms, when given the chance.

Culture as Mixture, Not Monolith

There was a moment in Asake’s Red Bull performance that stuck with me. The music switched to a salsa beat, and he danced with a partner, fluid and natural. It signaled a culture mix—singing in Yoruba over a Latin American rhythm. The transition was so smooth it became a statement: this is how easily cultures can mix when there’s mutual respect and genuine curiosity.

When a playful Puerto Rican meets a playful Nigerian, they connect through shared joy. But their different cultural expressions add depth. That difference isn’t a barrier, it’s an invitation.

Consider the lineage: Reggaeton is Caribbean music. And at the heart of Caribbean music, beneath the layers of Spanish guitar, Indigenous influences, and island-specific innovations, are African rhythms. The drums, the polyrhythms, the way percussion drives everything forward. These came through the transatlantic slave trade, survived centuries of transformation, and became the foundation on which new cultures built their own distinct sounds.

Puerto Ricans took drums and rhythmic structures that originated in West Africa and, over generations of mixing with other influences, made them distinctly Puerto Rican. Culture shows us how people inherit the past and, instead of just preserving it, remake it for the present. The result isn’t African music, and it isn’t purely Puerto Rican invention; it’s a transformation, evolution, something new built on ancestral foundations.

But here’s where ownership gets complicated. When that transformed culture becomes globally valuable—when Reggaeton dominates charts, when Afrobeats becomes the sound of summer—who claims ownership? The communities that evolved it over generations through collective participation, or the corporations and platforms that package it, distribute it, and profit from its reach?

The music industry has an answer: whoever owns the master recordings, whoever controls the publishing. But culture doesn’t work like that. You can own a song. You can’t own a sound that emerged from centuries of communal creation. And yet, that’s exactly what gets attempted when culture moves from the margins to the mainstream.

Why The Arts Matter

Some dismiss music and the arts as frivolous, especially given everything wrong with the world. But their ability to keep us connected, spiritually grounded, alive in our bodies, I think that’s wildly understated.

Some say Puerto Ricans celebrating through music while still lacking independence from the US is misguided energy. But in my experience, the “little things” like music and the joy it creates can be everything to someone. It’s not just entertainment or a paycheck for those who make it. It’s a source of life. It’s spiritual.

I saw this at Asake’s Red Bull Symphonic concert. The moment “Fuji Vibe” came on, the crowd went wild. Nigerians in the audience recognized it as what would take them close to home. You could see the fascination in the eyes of those who didn’t understand the language, the same way I felt watching Bad Bunny perform without understanding Spanish. Connection happened anyway. That’s what music does: it bypasses the need for translation because what it’s actually transmitting isn’t just words. Its identity, memory, home.

Maybe that’s exactly what makes it threatening. Because if people can find connection, spiritual grounding, and joy through their own cultural expressions—if they can feel complete without asking for permission or waiting for validation—then the systems built on making people feel inadequate start to lose their grip.

The Decentralization of Culture

The numbers tell the story that power doesn’t want to hear.

Bad Bunny sings in Spanish, the fourth most spoken language in the world, with over 600 million speakers. Asake sings in Yoruba, one of the top 40 languages spoken globally, fourth in Africa, with over 50 million speakers. These aren’t niche markets. They’re massive audiences that don’t need English as a mediator, don’t need Western approval to validate what they already know is powerful.

I remember the late Virgil Abloh in conversation with Tremaine Emory of Denim Tears, talking about how “American” culture is overused, how world pop culture is shifting and moving. The center is no longer holding because there are multiple centers now. Culture is decentralizing.

That’s what terrifies the old guard. Not that other cultures exist—they’ve always existed. But that they no longer need permission to be seen, no longer need to translate themselves to be valuable, no longer need validation from the institutions that used to control what counted as “global” or “mainstream.”

When Bad Bunny performs entirely in Spanish at the Super Bowl and becomes the most-streamed artist on the planet, he’s proving that the gatekeepers were never actually necessary. The audience was always there. The culture was always powerful. What’s changed is that the platforms—streaming, social media, global tours—have made it possible to reach that audience directly.

Culture as Identity and Threat

Culture answers fundamental questions: Who are you? Where are you from? What do you carry with you?

We all have personality traits independent of culture—temperament, disposition, the things we’re born with. But after that, culture takes hold. The combination creates who we are. Not just nature and nurture, but nature and culture.

Culture is what makes a group of people unique while connecting them to something larger than themselves. Its memory held in music, in movement, in how you gather and celebrate. It’s history that doesn’t need to be written down because it lives in bodies, in rhythms, in the way certain sounds make you feel at home even thousands of miles from where you were born.

Perhaps that’s exactly why it’s so threatening to power structures built on homogeneity and control. Because when people are rooted in who they are, connected to where they come from, and unapologetic about expressing it, they become much harder to control. Harder to sell to. Harder to convince they’re incomplete without whatever product or narrative you’re pushing.

Cultural expression at this level isn’t rebellion for rebellion’s sake. It’s simply people refusing to shrink themselves, refusing to translate their joy into something more palatable, refusing to wait for permission to take up space. And that refusal, that simple act of being fully yourself, becomes radical in systems designed to make you feel like you need validation to exist.

What We’re Actually Witnessing

I’m still working through all of this, but here’s where I keep landing:

Uninhibited cultural expression is a form of resistance. Not because it’s trying to be, but because joy that doesn’t ask for permission is inherently radical in systems built on scarcity and control.

The powers that be prefer culture that can be commodified, sanitized, and controlled. Culture that fits into marketing demographics and doesn’t ask uncomfortable questions. Culture that can be packaged, predicted, and profited from without disrupting the existing order.

But real culture—the kind that makes older Puerto Ricans weep with recognition, the kind that makes Nigerians in diaspora feel at home, the kind that requires bulletproof vests at award shows—that culture is dangerous precisely because it’s alive. It moves. It mixes. It evolves through collective participation across generations. It refuses to stay in the box you built for it.

The fear isn’t really about the music or the language or the dance. The fear is about what happens when people remember who they are, celebrate it loudly, and refuse to shrink it for anyone’s comfort. When they build audiences so large that they don’t need traditional gatekeepers. When they create on their own terms and prove that the “mainstream” was never actually the only stream—it was just the only one with the power to make itself visible.

That kind of memory, that kind of joy, that kind of power—it’s uncontrollable. And control is what these systems want most. Control over who gets seen, who gets heard, and who profits when culture moves from the margins to the center.

The question isn’t just who owns culture. It’s whether culture can even be owned when it’s this alive, this communal, this resistant to being reduced to a product.

Bad Bunny in a bulletproof vest isn’t just about one artist’s safety. It’s about what happens when a culture that was supposed to stay contained breaks through every barrier put in front of it. When it becomes undeniable, unavoidable, too powerful to ignore.

That’s what terrifies power. Not the culture itself, but the proof that it was never actually in control to begin with.

These are ongoing observations. I’m still thinking through these connections, still watching how culture moves through the world and why it matters. This isn’t a conclusion—it’s a conversation I’m having with myself, and now with you.

I really enjoyed reading this!.